28 November 2016

KC-390 airlifter (photo : NZHerald)

The listed Brazilian company has been making planes since 1969; it is a big global player in commercial jets with up to 130 seats, and based on its revenue from aircraft making, vies with Canada's Bombardier for the third spot behind Boeing and Airbus.

In nearly 50 years of business, Embraer has delivered more than 8000 aircraft in more than 90 countries, including the tough, small Bandeirante that flew on regional routes in New Zealand for more than 20 years to 2001.

The KC-390 was conceived in 2009 as a way of diversifying Embraer's revenue, and it has pitched the company into the medium lift market dominated by Lockheed Martin's Herc, a plane first developed in the 1950s, but whose latest model is still seen as the inside runner for New Zealand's next tactical lift purchase.

Embraer says it has been able to start with a clean sheet, and use expertise and technology from its commercial and corporate jet divisions to make a plane that can not only carry big loads, but also get places as much as a third faster than turbo-prop equivalents. It flies at up to 870km/h while still being able to use short and underdeveloped runways.

KC390 frontview (photo : KeywordsKing)

The company is also promoting its versatility, not only as a cargo carrier but also a multi-mission plane that can be used as a fuel tanker, medevac aircraft and for fighting fires, dropping paratroops and search and rescue.

Customers can also opt for a range of self protection systems, including radar warning receiver, a laser warning system, missile approach warning, and the ability to fire protective chaff and flares.

Embraer is aiming to have the KC-390 certified for military use by the end of next year, is also seeking civil aircraft certification - which it hopes to gain early in 2018 - and is already talking to one potential buyer.

The company began developing a test flight and plane manufacturing base in 2001 at Gaviao Peixoto, a sprawling 16sq km site on the high plains of Sao Paulo. Today the area is covered by 13ha of buildings and is still growing.

In one of the massive buildings, the KC-390 wing and fuselage construction line is busy assembling wings (in two parts) and the fuselage (in three parts) of planes destined for its first customer and development partner - the Brazilian Air Force, which has signed up for 28 of them. Several other defence customers are close to confirming orders.

KC390 Medevac version (image : Embraer)

Commercial partners in Portugal, Argentina and the Czech Republic make components for the plane, but the bulk of itis sourced from Brazil.

The gleaming assembly building is heavily populated by robots, which perform the repetitive task of precision drilling more than 60 per cent of the holes, through which they drive the titanium fasteners that hold the plane together.

Two of those planes are being made to be stretched, bent and possibly buckled in static stress tests that run around the clock in a nearby hangar. Massive weights are hung from the plane to push it to 150 per cent of its maximum tolerance.

Then there is fatigue testing of another complete plane over 45,000 hours of simulated flying - three times the estimated average lifespan of an aircraft in typical military service.

They have undergone ground vibration tests and lightning tests and are likely to end up in museums.

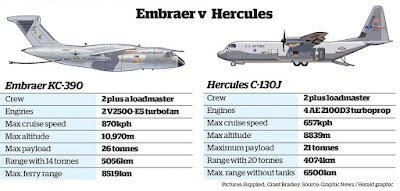

KC390 versus C130J (image : Embraer)

Like other aircraft, the KC-390 began its life in a computer, followed by the construction of an "iron bird" - a two-level steel rig covering about a third the size of a rugby field.

All the aircraft's hydraulic, avionics and flight control systems snake over this Mecanno-like structure and are run and monitored for years. On some commercial jets, the "iron bird" has been running for 15 years.

Failures and glitches can be introduced to assess how systems react and engineers can also sort out problems in real time if airborne planes need information from the ground.

Before certification, the plane will be deep frozen for days in a refrigerated hangar in Florida to test systems, operated in an Arctic environment and then tested in strong crosswinds in Southern Chile.

(NZ Herald)

KC-390 airlifter (photo : NZHerald)

The listed Brazilian company has been making planes since 1969; it is a big global player in commercial jets with up to 130 seats, and based on its revenue from aircraft making, vies with Canada's Bombardier for the third spot behind Boeing and Airbus.

In nearly 50 years of business, Embraer has delivered more than 8000 aircraft in more than 90 countries, including the tough, small Bandeirante that flew on regional routes in New Zealand for more than 20 years to 2001.

The KC-390 was conceived in 2009 as a way of diversifying Embraer's revenue, and it has pitched the company into the medium lift market dominated by Lockheed Martin's Herc, a plane first developed in the 1950s, but whose latest model is still seen as the inside runner for New Zealand's next tactical lift purchase.

Embraer says it has been able to start with a clean sheet, and use expertise and technology from its commercial and corporate jet divisions to make a plane that can not only carry big loads, but also get places as much as a third faster than turbo-prop equivalents. It flies at up to 870km/h while still being able to use short and underdeveloped runways.

KC390 frontview (photo : KeywordsKing)

The company is also promoting its versatility, not only as a cargo carrier but also a multi-mission plane that can be used as a fuel tanker, medevac aircraft and for fighting fires, dropping paratroops and search and rescue.

Customers can also opt for a range of self protection systems, including radar warning receiver, a laser warning system, missile approach warning, and the ability to fire protective chaff and flares.

Embraer is aiming to have the KC-390 certified for military use by the end of next year, is also seeking civil aircraft certification - which it hopes to gain early in 2018 - and is already talking to one potential buyer.

The company began developing a test flight and plane manufacturing base in 2001 at Gaviao Peixoto, a sprawling 16sq km site on the high plains of Sao Paulo. Today the area is covered by 13ha of buildings and is still growing.

In one of the massive buildings, the KC-390 wing and fuselage construction line is busy assembling wings (in two parts) and the fuselage (in three parts) of planes destined for its first customer and development partner - the Brazilian Air Force, which has signed up for 28 of them. Several other defence customers are close to confirming orders.

KC390 Medevac version (image : Embraer)

Commercial partners in Portugal, Argentina and the Czech Republic make components for the plane, but the bulk of itis sourced from Brazil.

The gleaming assembly building is heavily populated by robots, which perform the repetitive task of precision drilling more than 60 per cent of the holes, through which they drive the titanium fasteners that hold the plane together.

Two of those planes are being made to be stretched, bent and possibly buckled in static stress tests that run around the clock in a nearby hangar. Massive weights are hung from the plane to push it to 150 per cent of its maximum tolerance.

Then there is fatigue testing of another complete plane over 45,000 hours of simulated flying - three times the estimated average lifespan of an aircraft in typical military service.

They have undergone ground vibration tests and lightning tests and are likely to end up in museums.

KC390 versus C130J (image : Embraer)

Like other aircraft, the KC-390 began its life in a computer, followed by the construction of an "iron bird" - a two-level steel rig covering about a third the size of a rugby field.

All the aircraft's hydraulic, avionics and flight control systems snake over this Mecanno-like structure and are run and monitored for years. On some commercial jets, the "iron bird" has been running for 15 years.

Failures and glitches can be introduced to assess how systems react and engineers can also sort out problems in real time if airborne planes need information from the ground.

Before certification, the plane will be deep frozen for days in a refrigerated hangar in Florida to test systems, operated in an Arctic environment and then tested in strong crosswinds in Southern Chile.

(NZ Herald)